On 25th May 2020, George Floyd was added to the heartbreakingly long list of names of Black people who have been murdered due to the colour of their skin. You can see these names emblazoned on the news and across social media hashtags and yet, for many Black people like me, these names read like the stories we were told growing up – the story of our unending suffering. To say that Black people live in fear is not hyperbole. When the people whose job it is to protect you, murder you enmass – how can you not be afraid?

In an effort to minimize the impact of institutional racism on global police forces, I’ve seen a few people cite one of psychology’s most controversial studies – the Stanford prison experiment. In the study led by Philip George Zimbardo, participants were placed in a prison-like setting and given uniforms that gave them the role of either a prisoner or guard. In just 6 days, these seemingly normal men abused their power as guards and the study turned into a lesson that, if given the chance and if placed in the right situation, anyone can be corrupted. If only it were that simple.

Analyzing [police corruption] as a product of race-blind situational forces erases its deep roots in racial oppression. – Ben Blum

Replications of the study instead proved that our behaviours largely conform to our preconceived notions. Sadly, these notions have been shaped by: school systems that jump to expel black students, white-washed media, news stories that frame Black people as thugs, jobs that fail to give Black people wage parity, fashion houses that use racist designs as marketing ploys – all of which facilitate corruption by painting the picture that in every sense, Black lives don’t matter.

Racism and prejudice seep into every area of life and is even one of the reasons why I created this website. ‘Fashion is Psychology’ was born out of my undergraduate thesis which explored how the murder of 17 year old Trayvon Martin was treated in February 2012. As the news stories and hot-takes came flooding in, I couldn’t shake a comment from American Talk Show Host Geraldo Rivera “I think the hoodie is as much responsible for Trayvon Martin’s death as much as George Zimmerman was”. While it’s true that clothing style and race are integral to impression formation, as we’ve learnt from Zimbardo’s study, awful acts are neither situational or clothing dependent.

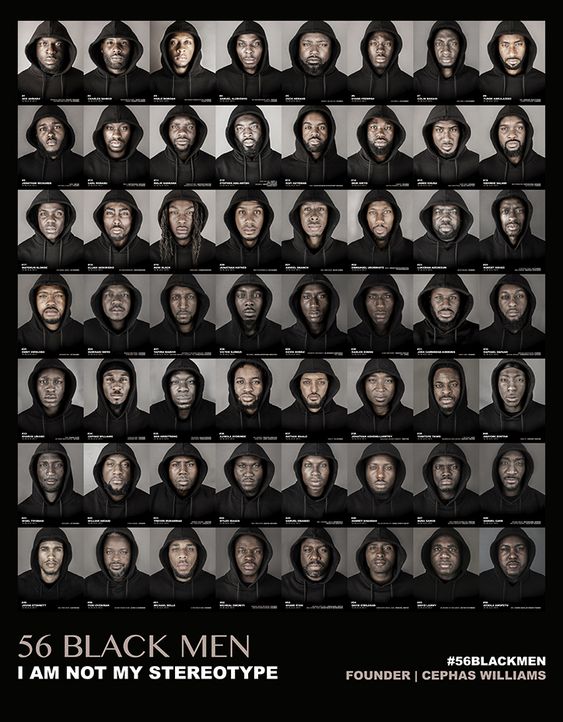

Trayvon’s hoodie became the symbol of #BlackLivesMatter and sparked movements from the Million Hoodie March in New York in 2012 and the 56 Black Men campaign in the UK by entrepreneur Cephas Williams just last year. Both movements shed light on how clothing styles are used as a weapon against Black people, an excuse for White fear, when in reality, racism is so deeply entrenched in the fabric of society it supersedes choice of dress.

Ironically, hoodies are an integral part of the streetwear market which as of 2017 was valued at $309B. Streetwear and the wider Fashion industry at large consistently draw from Black culture, but rarely uplifts Black talent. As BOF highlighted, Off-White’s Virgil Abloh and Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing are the only Black creative directors at major brands, and “there are almost no Black CEOs”. Even Abloh himself has recently come under fire, firstly for an initial donation of only $50 to the Black Lives Matter movement (Abloh is currently worth an estimated $4M) and then for his largely White staff – proving that the success of a few Black people is not enough to eradicate Fashion’s race problem. The situation in front of the camera is getting slightly better with some studies showing that the number of BAME people featured in marketing campaigns has increased in recent years. However, as my own research has pointed out, considering the strength of the Brown Pound and the fact that Black consumers are willing to pay more for products advertised by Black models, it’s shocking that representation is still a topic of discussion.

So where do we go from here?

Fashion has a duty to support Black people

A value of a brand is no longer dictated by the clothes they design. Consumers need to know where a brand stands on various socio-political issues. They not only need to show support they need to embody the ideals they’re espousing in their Instagram posts. The recent actions of fast-fashion brand Pretty Little Thing is a great example of how the tides of change are dissolving Fashion’s old “thoughts and prayers” approach to activism. In the wake of Floyd’s death, influencer Jackie Aina called out Pretty Little Thing (among others) for capitalising on Black culture via their aesthetic but staying silent in the face of Black suffering. Their initial response of posting an illustration of a black (literally black) hand holding a White one was met with a wave of criticism. The brand have since teamed up with recording artist Saweetie to create a line where all of the proceeds go to the Black Lives Matter organisation.

Donating is one thing but more needs to be done. The industry has a duty to use its privilege to hire more Black talent, to place more Black people in senior positions, to amplify Black voices and to invest in more Black businesses.

Psychology has a duty to support Black people

As highlighted by researchers Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan (2010), “individuals from Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic (WEIRD societies) make up the bulk of samples in psychological research. This is problematic because it skews generalizations about human behavior overall since although 80 percent of research participants are from WEIRD societies, people from these societies represent just 12 percent of the world’s population.”

Education has been hailed as the first line of defence against racism but if the literature is already skewed and Black voices are silenced, how much can we really learn? Studies investigating racism in particular can fall short when it doesn’t include Black researchers to provide the nuance needed to produce the robust results demanded of the field. The Psychology workforce is also overwhelmingly White. From Black academics to Black therapists, more targeted support is required to even the playing fields.

I wish I could say that fear of the police and institutionalised racism was the only fear Black people have. There’s also the fear that you’ll have to always work 10 times harder than your White counterparts to achieve an equal level of success. The fear that the way you act will be a reflection of your entire race when you find yourself (yet again) being the only Black person at school or work. Then there’s the fear of having to continually explain your existence and why your life matters. It’s troubling to know that it took so many lives to be lost for us to see real change but change is coming and it’s time for everyone to get on board.

Visit our ‘Culture’ section for more readings on Fashion, Psychology and Race.

Header image: Sébastien Thibault

Join the discussion One Comment